In an earlier post, I looked at four messianic types found in Judaism and how they are all fulfilled by Jesus. However, this is not really the biggest objection Jews have about Jesus. Their biggest objection is the idea that God could become man. While I will not fully respond to that here, I just want to sketch an outline of how this could be responded to. (And I will do so here from a biblical perspective, although I am trying to think through how one might explain Chalcedonian metaphysics in language familiar to Jews and hope to write something on this in the future.)

Firstly, we should think about what the major theme of the Torah is: God coming to dwell with man. The Torah opens with God creating a world in which to dwell, and placing a man in the garden to dwell with. However, that man sins and hence distances himself from God. Looking at the overall narrative arc of Genesis-Exodus, we see it ends with man being given the tabernacle so that he might dwell with God again. The center of the whole Torah then in the Day of Atonement, the one time the high priest can fully enter God’s presence in the Holy of Holies. The Torah ends in Deuteronomy with the people about to enter Eretz Yisrael, the land where God will dwell with them. Moses mentions “life and death” and “good and evil” in his closing speech, a reminder back to the garden. This land will be like the garden of Eden. While Israel fails in its task, the prophets look forward to a time when the whole world will be filled with the knowledge and presence of God.

Thus, the incarnation is merely God coming to dwell with man most perfectly. The incarnation is not the pagan deification of a man, or even a pagan demigod, but rather the perfect union of two distinct natures, divine and human, in a singular divine person, so that each remains fully present.

But why should we expect this to happen through an incarnation rather than just the presence of God filling the world? I want to look at two themes noticed in common by Rabbinic literature and the New Testament.

Firstly, the incarnation of Wisdom. Bereshit Rabbah 1:1 glosses the opening verse of Genesis this way:

The Torah is saying: ‘I was the tool of craft of the Holy One blessed be He.’ The way of the world is that when a flesh-and-blood king builds a palace he does not build it based on his own knowledge, but rather based on the knowledge of an artisan. And the artisan does not build it based on his own knowledge, but rather, he has [plans on] sheets and tablets by which to ascertain how he should build its rooms, how he should build its doors. So too, the Holy One blessed be He looked in the Torah and created the world. The Torah says: “Bereshit God created” (Genesis 1:1), and reshit is nothing other than the Torah, as it says: “The Lord made me at the beginning of [reshit] His way” (Proverbs 8:22).

(This passage is cited by Rashi in his commentary on Genesis as well.)

The “beginning” in which God made the world is divine Wisdom. In this early Rabbinic literature, this Wisdom is the Torah. Strictly speaking, we have no issue with this. Sirach, a Jewish book which made it into the Catholic canon but not the Jewish canon, identifies Wisdom with the law of Moses (Sir 24:23 [32-33 DRA]). However, we also identify Wisdom as more than this. We understand Wisdom as a divine person.

In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. He was in the beginning with God; all things were made through him, and without him was not anything made that was made. (John 1:1-3)

Wisdom, in the Christian understanding, is a divine person. This actually has some parallel in the Jewish tradition as well. Wisdom comes to be understood in Kabbalah as a divine emanation (a sephirah). This is not to say to say that Kabbalah teaches Trinitarianism, but both understand that Wisdom is more than just the written Torah.

The Catholic understanding then is that Wisdom comes to us not only as the written Torah, but also as the incarnate person of Jesus of Nazareth. Jesus is the incarnate Torah. (This is a major theme in Pope Benedict XVI’s Jesus of Nazareth series.)

Secondly, there is an idea in Jewish mysticism called Adam Kadmon, the primordial man. This concept is found in Philo as well in his idea of the “heavenly man.” It then gets developed in Kabbalistic sources, starting with the Sefer Yetzirah but continuing in an important place all the way to present Kabbalistic theology.

The idea behind this is that before God made the Adam Rishon, the first man whom we encounter in Genesis, He first made Adam Kadmon, the primaeval man who contained all things in himself. The whole world is modeled on Adam Kadmon, and when the universe is fully perfected in the messianic age, it will reform Adam Kadmon.

A contemporary of Philo had a similar view:

Thus it is written, “The first man Adam became a living being”; the last Adam became a life-giving spirit. But it is not the spiritual which is first but the physical, and then the spiritual. The first man was from the earth, a man of dust; the second man is from heaven. As was the man of dust, so are those who are of the dust; and as is the man of heaven, so are those who are of heaven. Just as we have borne the image of the man of dust, we shall also bear the image of the man of heaven. (1 Cor 15:45-49)

St. Paul sees there as being both an earthly man (Adam) and heavenly man (Jesus). While many contemporary exegetes read this as about the resurrected Jesus, Matthew Levering points out that St. Cyril of Alexandria and St. Thomas Aquinas rightly understood this passage about Jesus’s heavenly origins (Reconfiguring Thomistic Christology, 77-95).

The similarities between this later Kabbalistic development of Philo and Catholic theology did not go unnoticed by later theologians. I will point out two. (I am including lengthy blockquotes to prove my point. Feel free to skip them. I have bolded and italicized the important parts.)

Firstly, St. Lawrence of Brindisi (a Doctor of the Church):

If anyone considers the hidden wisdom within the opening words of Genesis, he will see that in them the entire plan of the creation of the world and of all things is open and unfolded. Inasmuch as from the resolution of these first words into their constituent elements and from the different arrangement of these same words among themselves, the whole utterance in Hebrew is comprised of twelve words: av bebar reshith shavath bara rosh esh shath rav ish brith tov, i.e. The Father in the Son—or by the Son, or in the Son in the beginning and end—created the head, fire, the fundament of a large man in a good covenant. In the last word, the initial letter teth is changed to taw, which is very common among the Hebrew letters with the same pronunciation.

How wonderfully apparent in this reading of the initial words of Genesis is the first explanation that we considered, viz., that God the Father created the world in His Son or with His Son or by His Son! However, the Son is said to be the beginning and the end, or the repose, according to Scripture: I am the Alpha and Omega, the beginning and the end. However, in interpretation above, what does “large man” mean? It means, the world itself. Just as a man is a small universe, so the universe is a large man. Hence, the image advantageously and most fittingly compares the three worlds of the universe—the intellectual, the heavenly, and the corruptible—to the three anatomical regions of the human body. The first is the head, the second extends from the neck to the navel, and from the navel to the feet is the third region. In the head, the brain is the source of thought; in the breast, the heart is the source of motion, life, and heat; and finally in the third part are organs of procreation, the principle of generation. Likewise, in the universe the intellectual part is the highest, since it was created for the purpose of understanding. The second part comprises the heavens, the principle of motion and of life and of heat. The sublunary region is most obviously connected with generation and corruption. Moses called the first part the head, because it is the source of all thought. He called the second fire because the heavens are thought to be of a fiery nature. He called the third part the foundation of a large man because by it the entire body of a man is grounded and sustained. Yet since between these parts there is a covenant of everlasting peace and friendship, He added in a good covenant, the covenant of which Jeremiah spoke: Thus says the Lord: When I have no covenant, i.e. this covenant of peace and friendship, with day and night, and I have given no laws to heaven and earth. That covenant certainly is good, because it is directed toward God, who is good itself. (Commentary on Genesis, trans. Craig Toth, 6-7).

Lawrence connects the structure of creation to this great man. He also points out that the world was made for the sake of covenant. In other writing, Lawrence affirms the Absolute Primacy of Christ, so these two aspects are brought together for this. While Lawrence does not make the connection with Kabbalah explicit, given his familiarity with Kabbalah (Cf. his De numeris amorosis), it is almost certainly implied here.

Secondly, Matthias Joseph Scheeben:

The overall structure of the universe can be described after the analogy of the human organism so that the realm of spirits forms the bright head of the universe, towering over all the rest, the realm of material nature—its other members, and man as the living center of the whole—its heart. However this does not prevent mankind from appearing as the head of the whole universe in the supernatural order, in that mankind united with the Logos towers over the angels both in dignity and also in spiritual perfection…

Related to the Platonic interpretation in still other points also, and perhaps at its foundation, is the extremely interesting grouping of the worlds in the Kabbalah; but on the other hand, too, once it is freed of its fantastic frills, or is traced back to its original content in unadulterated Jewish theology as contained in the little Book of Yetzirah, which very probably goes back to the time of the Babylonian Exile, this cosmology corresponds altogether to the biblical and patristic interpretation. It understands the “world” from the perspective of a divine product through emanation and expression of the light hidden within God or of the wisdom of God and hence divides the worlds according to the different ways in which the divine Wisdom is manifested. 1. The mundus emanationis (or radicationis, mundus Aziluth from אצל ), which is nothing other than the consubstantial product of God’s Wisdom, the sapientia genita [begotten wisdom], which on the one hand, considered ad intra as the Word and Image of God, is God Himself and Creator, but at the same time on the other hand, considered ad extra, is the hypostatized idea and the ideal of the external world and, as in Sacred Scripture “primogenita ante omnem creaturam,” “the firstborn before all creatures” (Sir 24:5), was thus called κόσμος νοητός or mundus intelligibilis [intelligible world] by the Church Fathers. 2. The mundus creationis (mundus Beriah from בדא , creation understood in contrast both to emanation from God and also to formation out of some material), the world of pure intellects or of living, creative Wisdom, which is the proximate external likeness of God’s internal wisdom, still shares physical invisibility with the sapientia genita, and hence is combined with the latter also from this perspective as mundus intelligibilis and invisibilis, but as distinct from it is merely the invisible throne thereof. 3. The mundus formationis (mundus Jezirah from יצד in the sense of harmonious formation and rhythmic movement), in which God’s wisdom is manifested specifically as numbering and measuring according to unchangeable mathematical laws (cf. Sir 1:9), or as artfully ordering and moving: the material heavens or the physical cosmos in the modern sense of the term as the sum total of worldly bodies and of course along with that the earth also, insofar as similar mathematical laws rule with regard to it and on it, especially in the world of tones. 4. The mundus factionis (mundus Asiah from עשׂה in the sense of the simple production even of a fleeting product for temporary usefulness): the region of material life subject to generation and corruption, or the world of the beings themselves that live in this way and make use of earthly matter, or the earthly world, in contrast with which the other worlds are all described as heavenly. In this lowest world man stands as the crown thereof; however he is intertwined with it only by his body and the lower part of his soul, but through his reason, which knows the regularity [Gesetzmässigkeit] of the mundus formationis, he is akin to the latter also and rules it, likewise through the higher side of his reason, by which he knows what is purely spiritual and God Himself, he is close to the mundus creationis and, being thus the sum total of all three created worlds, also represents outwardly more than any single one of them the mundus emanationis, in which all three have their highest ideal. Now insofar as man at the same time is not so much a world himself as he is king of the world, the eternal ideal that is represented by him—the Son of God as Ruler of all worlds or as born heir of the Creator of all worlds—is also called by him the Primordial Man, Adam kadmon. (Handbook of Catholic Dogmatics, vol. 3, n. 128, emphasis added)

Scheeben elsewhere endorses the Primacy of Christ, although as understood according to the Salamanticenses understanding.

A major objection will be raised at this point: Adam kadmon is created, whereas the Son is undercreated. However, if we understand Adam kadmon according to the eternally predestined human nature of Christ, which is first in the order of intention according to many theologians (including both above authors), then it fits perfectly. The whole world is modeled on the incarnation, most especially humanity. In the end, all the just will be united to the incarnation as part of the mystic body of Christ (the totus Christus).

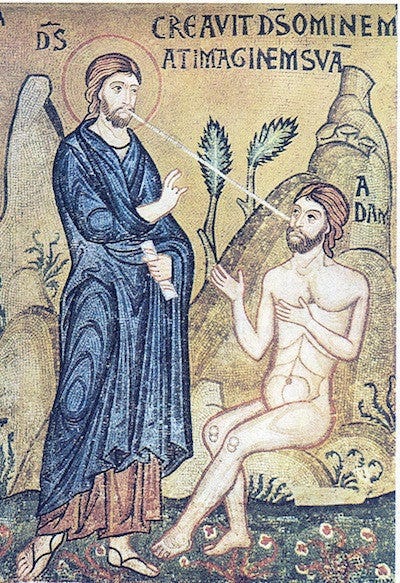

Indeed, many Catholic visionaries have even suggested that Adam looked identical to Jesus. This has a long iconographic tradition as well.

None of this is to say that Kabbalah is in line with Catholic orthodoxy. There is quite a bit of stuff in its which has close parallels with Gnosticism. (Scheeben even goes further than I likely would in his total endorsement of the Sefer Yetzirah, which Scheeben dates far earlier than I probably would.) But I do think it shows how, independently of one another, both Jewish and Christian exegetes came to similar conclusions about the role of this heavenly/primaeval man in both creation and eschatology.

Why should we think though that Adam kadmon is the messiah? These are two distinct things in Jewish theology. However, if we understand the world as created for the sake of the messiah (a common Jewish belief), then it makes perfect sense that the messiah is Adam kadmon. Indeed, the connection between the messiah and Adam kadmon is found within the Jewish tradition itself (even if only as an opinion).

Rabbi Shimon ben Lakish said: [The creation of Adam was] last [aḥor] among the acts of creation on the last day, and first [kedem] among the acts of creation on the first day. This is in accordance with the opinion of Rabbi Shimon ben Lakish, as Rabbi Shimon ben Lakish said: “And the spirit of God was hovering over the surface of the water” (Genesis 1:2) – this is the spirit of the messianic king, as it says: “The spirit of the Lord will rest upon him” (Isaiah 11:2). If a person is meritorious, it is said to him: ‘You preceded the ministering angels’; if not, it is said to him: ‘A fly preceded you, a gnat preceded you, this earthworm preceded you.’ (Bereshit Rabbah 8.1)

Furthermore, if the world was patterned on the Wisdom/Torah and on Adam kadmon, why should we think that these two are different. Thus, I think Christians are perfectly sensible in identifying the dwelling of God with man, Wisdom, the Torah, Adam kadmon, and the messiah all with Jesus of Nazareth.

In conclusion then, I do not think the idea of the incarnation, if understood properly, is actually as foreign to the Jewish tradition as most Jews believe it to be. Hopefully in a future article I can take up the metaphysical issues more directly, but at least at a biblical and mystical level, it makes perfect sense.

Did the Jewish position against incarnation harden under the influence of islamic philosophical and theological currents?